The Trevi Fountain

The Trevi Fountain is one of Rome’s most famous monuments. In late Baroque style, it is the most famous of the more than 2000 fountains that adorn the streets and squares of Rome. Pope Urban VIII (of the Barberini family) commissioned its construction in 1640 along with a series of monuments in the city and Lazio.

Location:

Piazza di Trevi

Built by:

Bernini, Michetti, Vanvitelli, Salvi between 1410 and 1762

What to see:

Fontana di Trevi, statue of Oceano

Opening hours:

The square is open h24

Price:

Monument open to the public

Transport:

Metro station Spagna

Top selling tickets on ArcheoRoma

There are various theories regarding the name of the Trevi Fountain:

During the sixth century, at the time of the last Gothic war (535 – 554 AD) the 11 aqueducts supplying Rome were cut on the orders of Vitiges, king of the Ostrogoths, when he besieged the city of Rome in 537 AD, or their channels were bricked up by Belisarius (the Byzantine general defending Rome), to prevent the enemy from gaining access to the city by crawling through them (a tactic Belisarius himself had used to conquer the city of Naples the previous year).

Following the siege some of the aqueducts were restored, but by the ninth century those that were still functioning fell into a state of disrepair due to lack of resources for their maintenance, and the Romans went back to the practice of drawing water from the river, wells and local springs.

The original Acqua Vergine Antica aqueduct (in Latin: Aqua Virgo) was completed in 19 BC by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, the close collaborator, friend, son-in-law, and lieutenant of the Emperor Octavian Augustus. Its name literally means “Virgin Water” due to the legend that when Agrippa’s soldiers were looking for good spring waters to supply the aqueduct, a local maiden led them to a pure and uncontaminated source.

It ran almost entirely underground and was supported on arches only for the last two kilometres, when it entered the urban areas of ancient Rome. Although it too was cut during the siege of the Ostrogoths it was repaired several times and completely restored in 1453 by Pope Nicholas V.

It still flows to this day. The low calcium content of the waters of the aqueduct probably helped to preserve its channels from mineral deposits, so that it could be kept in use for long periods. Nevertheless, regular maintenance was necessary over the years and its waters had to be stopped several times for these vital interventions.

The source for the waters of this aqueduct is a series of natural springs that fed the river Aniene, the major tributary of the Tiber, 10 kilometres east of Rome (at the locality known as “Salone”). Despite the vicinity of this source the aqueduct has a length of 22 km, since it follows an indirect route, in order to ensure a continual gentle slope as it heads towards Rome.

For about 8 km it runs fairly straight as it follows the Via Collatina through underground channels, but it then abruptly turns north, crossing the Via Tiburtina and Via Nomentana, where it turns west to cross Via Salaria, cutting across reaching the park of Villa Ada. It then heads south-west, passing through the district of Parioli and the western edge of Villa Borghese. The Acqua Vergine goes under the Aurelian walls to finally enter the city centre, skirting the Pincio hill through the gardens of Villa Medici and descending to Piazza di Spagna, where it supplies the Barcaccia Fountain.

It continues south to supply the Trevi Fountain and then turns due west to provide water to the Four Rivers Fountain in Piazza Navona. In this area it originally supplied the Baths of Agrippa, the first public baths in Rome, for which purpose the aqueduct was originally constructed. Next to the baths there was a large artificial lake where visitors to the baths could swim and the used water flowed west from here into the river Tiber.

In the 1930s, due to contamination of the water during its course, a modern pressurised version of the aqueduct, the Acqua Vergine Nuova, which is still fully operational, was built to provide healthy drinking water.

Due to its increased hydraulic pressure it runs more straight when it reaches Rome, and thus has a much shorter overall length of 13 km. Branches of this sister aqueduct and the original Acqua Vergine Nuova now feed several fountains in the centre of Rome, such as those in Piazza del Popolo, the fountain of the Tortoises in Piazza Mattei and the Fontana del Nicchione on Via dei Fori Imperiali.

After the 6th century, the Aqua Virgo was restored and altered a number of times, including an intervention by pope Hadrian I in the 8th century. It no longer supplied the Baths of Agrippa and, according to some historical sources, it ended with a small fountain near the present site of the Trevi Fountain.

During the early Middle Ages, since the other aqueducts no longer flowed, wells were dug in order to provide the people with water and many ancient monumental fountains were dismantled in order to reuse their materials. Fountains at the time were low basins supplied by local springs, often near churches so that they could be used for religious rites and celebrations, such as the fountain of the Basilica of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere.

Starting in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance period, after the Popes brought the seat of the Curia (the papal administration) back to Rome from Avignon, some important new fountains were designed and built, including the Trevi Fountain and the fountain of Saint Peter’s basilica.

The first known image of the Trevi Fountain is a sketch dating to the year 1410, when it consisted of three basins side by side, into which water gushed from three spouts. In 1453, as part of a vast program of renewal of the city of Rome, Pope Nicholas V commissioned the sculptor and architect Bernardo Rossellino and the humanist architect and intellectual Leon Battista Alberti to renovate this fountain and the three pools were united as a broad rectangular basin, in front of a high crenellated wall from which water flowed from three holes.

Above them on the wall an inscription in Latin, surmounted by the papal coat of arms, stated that “The Pontiff Nicholas V, after embellishing the city with monuments, restored the conduit of the Acqua Vergine from its ancient state of abandonment in 1453”. In his De re aedificatoria (“On the Art of Building”), which he presented to Nicholas V in 1452, Alberti stressed the importance of having an efficient water infrastructure in Rome with the best water being used for public fountains. In 1570 another important restoration of the entire Acqua Vergine aqueduct was carried out by Pope Pius V.

The High Baroque architect and sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini created many artworks and monuments in the churches and public spaces of Rome during the papacy of Urban VIII (1623-44), of the Barberini family. After completing the massive bronze canopy or Baldachin in the Basilica of St. Peter’s in 1634, he was given the task of transforming the Trevi Fountain and the adjoining square, near the papal residence at the Quirinal Palace (Palazzo del Quirinale).

It was also quite close to the Barberini family palace (Palazzo Barberini) which had just been completed. The work was partly financed by an extremely unpopular tax on wine. In around 1640 Bernini enlarged the narrow square by demolishing some buildings and he changed the alignment of the fountain, so that it could be seen from the Quirinal Palace. It now faced south, which is its present orientation.

Bernini intended to construct two concentric semicircular basins, with a central pedestal just below the water level to support a statuary group, probably centred on the figure of the virgin known as “Trivia”, (a Roman epithet of the goddess Diana).

But funds for the ambitious project soon dried up (perhaps because the people cut back on their wine consumption!) and following the death of Pope Urban VIII the new pope, Innocent X of the Pamphili family, was reluctant to employ Bernini. He wanted a monumental fountain of his own to glorify his papacy and his family, and so he planned to use the waters of the Acqua Vergine for a new fountain with free-standing figures in front of the Pamphili family palace, in the centre of Piazza Navona about a kilometre to the west of the Trevi Fountain.

It seemed that Bernini’s arch-rival, the architect Francesco Borromini, might get the job, but Bernini was eventually awarded the commission. Known as the Fountain of the Four Rivers, it was completed in 1651.

In the early eighteenth century, a period in which the Late Baroque or Rococo style was predominant in art and architecture, a series of competitions were organized, in which several sculptors and architects took part, including the Italians Ferdinando Fuga, Luigi Vanvitelli and Nicola Michetti, and the French sculptor Edmé Bouchardon. Carlo Fontana suggested an obelisk standing over a rocky base (inspired by Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers) and Borromini’s nephew, Bernardo Castelli, submitted a plan with a column surmounted by a spiral ramp. Work on the Trevi Fountain was put on hold during the papacy of Innocent XIII (1721-24), whose family, the Conti, dukes of Poli, had recently bought some buildings in the square, in order to create a large mansion. A large monumental fountain would have damaged the newly built Palazzo Poli.

However the abandoned project to create a new Trevi Fountain was soon unearthed again and another competition was held by Pope Clement XII in 1730. When the Florentine Alessandro Galilei won there was a public outcry in Rome over this “foreigner” having been awarded the task, so he was replaced by the Roman Nicola Salvi, an architect in his early thirties, whose scenographic and harmonic plan arranged for the central part of Palazzo Poli to be demolished, to create more space the fountain’s central statuary group.

The horrified Conti family complained about the partial destruction of their new mansion, but the pope decreed that demolition would go ahead and work began in 1732.

The Trevi Fountain as we see it today basically corresponds to Nicola Salvi’s original intention. Water flows into a large shallow basin down a series of rugged rocks made of travertine stone, populated by sculpted allegorical figures, with Palazzo Poli acting as an imposing and grandiose backdrop.

The fountain was inaugurated three times by three different popes:

After thirty years of work the Trevi fountain had finally been completed in the form in which we now see it.

The Trevi Fountain has recently been extensively restored two times:

The Trevi Fountain consists of a rectangular basin placed in front of the scenic façade connected to the Palazzo Poli, which serves as an architectural backdrop. The architectural complex is composed of:

| Maximum height of the façade | 26.30 m |

| Total width of the façade | 49.15 m |

The façade of Palazzo Poli, completed in the 18th century as the monumental backdrop to the Trevi Fountain, is an extraordinary example of the integration between architecture and decorative arts. This building, adapted to harmonize with the grandeur of the fountain, embodies the principles of late Baroque classicism, combining balanced proportions with elaborate sculptural decoration.

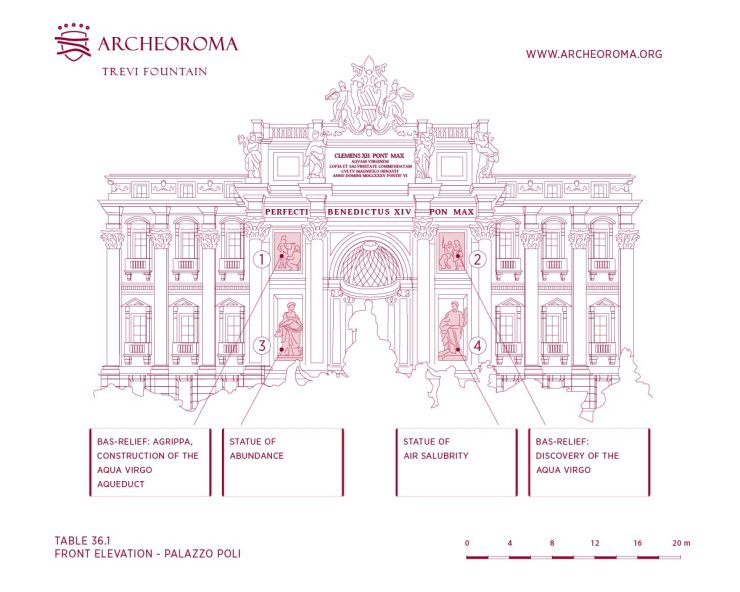

The first level of the Palazzo Poli façade, located directly above the sculptural ensemble of the Trevi Fountain, represents a masterful synthesis of architectural rigor and decorative symbolism. This section of the façade acts as a transition between the dynamic energy of the fountain and the monumentality of the palace, characterized by a solemn and refined compositional order. The structure is articulated with pilasters and cornices that create a symmetrical scheme, emphasizing the verticality of the façade. Architectural elements such as windows crowned with alternating triangular and curved pediments introduce rhythm and depth to the elevation, harmonizing with the overall composition. Though seemingly subordinate to the grandeur of the fountain, this portion of the façade plays a fundamental role in visually and symbolically uniting the different components of the ensemble.

The Main Elements of the Façade (Table 36.1):

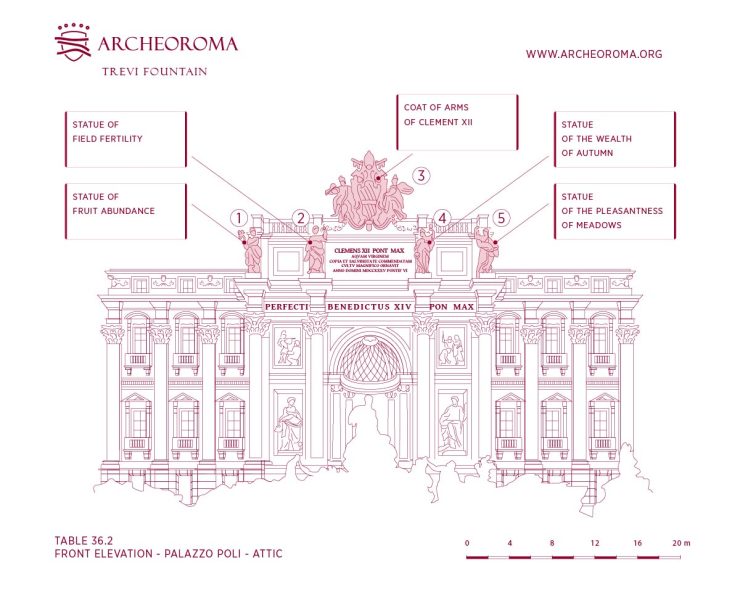

The attic of Palazzo Poli, located above the first level of the façade, represents the architectural and symbolic crowning of the monumental complex of the Trevi Fountain. This upper level, while maintaining the sobriety of the palace’s architectural lines, stands out for the richness of its sculptural decorations, which converge around allegorical themes of abundance and prosperity.

The attic is designed as a conclusive element, conceived to emphasize the central axis of the complex. The composition is dominated by the papal coat of arms of Clement XII, placed at the center of the structure—a clear reference to the pope who commissioned the fountain. This element, a symbol of papal power and continuity, is flanked by four allegorical statues that amplify its symbolic significance.

The Tavola 36.2 provides a detailed analysis of the main elements composing the attic:

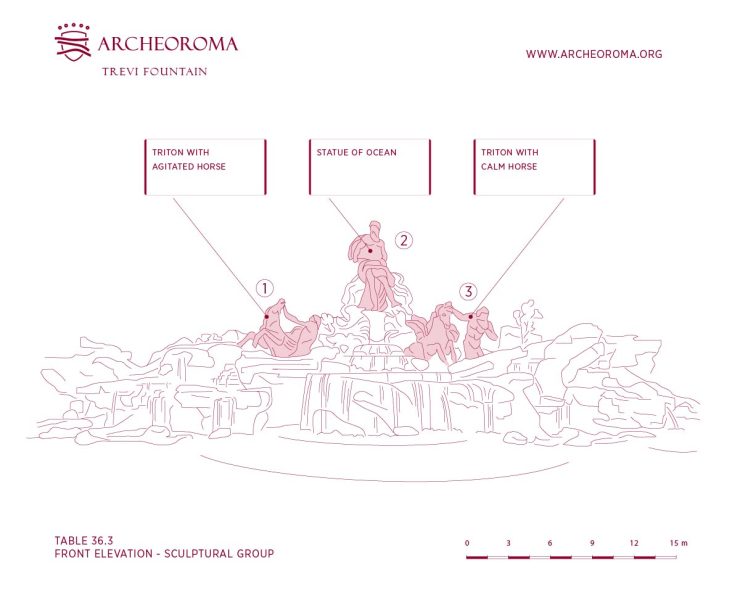

The central sculptural group of the Trevi Fountain, conceived as the narrative and symbolic focal point of the entire monument, represents an extraordinary synthesis of dynamism, allegory, and sculptural mastery. Created by Pietro Bracci in the 18th century, this artistic complex stands out for its Baroque theatricality and its ability to evoke the power and vitality of water.

The central sculptural group of the Trevi Fountain conveys a complex symbolic narrative about water. The figure of Ocean, at the center, represents the universal power of the waters, while the two tritons and the horses embody the duality of the sea: untamed force and vital resource. The contrast between the agitated horse and the calm horse emphasizes this dichotomy, creating a visual and thematic balance that enhances the theatricality of the work.

The sculptures integrate seamlessly with the architectural context and the perpetual motion of the water, amplifying the monument’s visual and symbolic impact. The mastery of Pietro Bracci, visible in the detailed rendering of the characters and the dramatic use of contrasts, elevates the sculptural group to a sublime example of Roman Baroque sculpture.

The practice of tossing a coin into the Trevi Fountain is well-known throughout the world, and has been made famous by songs and films such as Three Coins in a Fountain, and no self-respecting tourist can fail to follow this romantic custom. Less widely-known is the equally romantic (but more risky) tradition of the glass of water.

According to the legend if you visit Rome you must toss a coin into the water of the central basin, with your back to the fountain, flipping it with your right hand over your left shoulder. If you can turn round quickly enough to see the coin splash into the water, you will be sure to return to Rome one day.

This tradition dates back to the custom of the ancient Romans of throwing coins into water so that the gods would protect them if they travelled over the sea, and help them to return home safely. A variant of this legend, which inspired the movie Three Coins in a Fountain, says that if you throw three coins into the fountain at once, the following three things will come true:

This tradition is no longer in use, due to the poor quality of the constantly recycled water, and is little known today. In the past if a girl’s boyfriend had to leave the city for work or military service, she would make him drink some water taken from the fountain out of a new glass and then she would break it. This magic ritual was supposed to ensure his eternal fidelity, even when he was far away.

Today there is a safer version, which avoids the risk of having a stomach upset. The two lovers drink together from the so-called Fontanina degli Innamorati, or “Little Fountain of Lovers”, located to the right of the monument underneath the so-called asso di coppe (ace of cups), a sort of urn which stands on the balustrade that runs alongside to the road above. This small fountain has two jets of drinking water and in this way a couple can make sure that they will always remain faithful to each other.

In high season about 3,000 Euros are thrown into the fountain every day. The coins are fished out at dawn every day every night and given to an Italian charity called Caritas, which uses the money to fund a program of vouchers for the needy and poor of Rome so that they can obtain supermarket groceries. It is now illegal to take coins from the fountain, but thieves used to do this at night.

The most famous and elusive of them all was a certain Roberto Cercelletta, also known as d’Artagnan, the fourth musketeer. He managed to steal coins from the fountain using a rake and a magnet for 34 years while the police turned a blind eye. When the media reported that he was taking as much as a thousand Euros every night he was caught red-handed in 2002, although when the case went to trial judges never found a legal basis to charge him with a crime.

While the fountain was being built near the point where Via della Stamperia enters the square there was a pharmacy (although some say it was a barber’s shop), whose owner insisted on putting up a big sign which spoiled the view of the monument (some say he also criticised Nicola Salvi’s artistic decisions).

In order to prevent him from seeing the progress of the work, and to block the view of his shop sign Salvi therefore decided to erect a large urn made of travertine statue right in front of his premises. Due to its similarity to the “Ace of Cups” a playing card in the deck of cards commonly used in Italy, the Romans renamed it the Asso di Coppe.

On two recent occasions the waters of the Trevi Fountain turned red. In 2007 Graziano Cecchini, a self-proclaimed modern day “futurist artist”, poured red dye into the fountain. He pulled the same stunt again a decade later in 2017, this time claiming that it was an act of protest to raise awareness of government corruption, adding that the performance was intended to “shake people’s souls”, because Rome was ready to be “the capital of art, of life and of rebirth”.

Instead many commentator saw his actions as a pointless publicity stunt amounting to vandalism. Fortunately, in both cases, the red dye did not leave any permanent stains or marks on the monument.

There are many scenes in Italian and international movies featuring the Trevi Fountain. These are some of the most important scenes that have made cinematographic history.

In 1960 the Roman director Federico Fellini shot one of the most famous scenes from the film “La Dolce Vita” in the waters of the Trevi Fountain. The Swedish actress Anita Ekberg wades into the large basin of the fountain wearing a long dark evening dress and invites Marcello Mastroianni to join her, calling to him with the words “Marcello, come here! Hurry up!”.

In 1974, the director Ettore Scola paid tribute to the above-mentioned scene from “La dolce Vita”, by restaging the set and integrating it in his own film “C’eravamo tanto amati” (We All Loved Each Other So Much) to create the scene in which the hospital porter Antonio, played by Nino Manfredi, chances to drive into the square where he sees the aspiring actress Luciana, played by Stefania Sandrelli, with whom he has been in love for years.

In this comedy film from 1961 the conman Antonio, played by the actor Totò (Antonio de Curtis), pretends to be the nobleman Antonio Trevi who is the owner of the Trevi Fountain. Thanks to his sidekick Camillo, masquerading as another potential buyer, he swiftly manages to swindle 500 thousand liras out of an ingenuous businessman as a deposit for the sale of the Trevi fountain.

The Trevi Fountain is located two blocks southeast of the junction between Via del Corso and Largo Chigi (the continuation of Via del Tritone). It is situated in Piazza di Trevi between Via Poli to the west, Via della Stamperia to the east and Via delle Muratte to the south. The Quirinal Palace complex rises just 100 meters to the southeast on the Quirinal Hill.

The nearest metro station is Piazza di Spagna, 500 meters due north. From here you should walk past the Spanish Steps and go along Via di Propaganda and Via di Sant’Andrea delle Fratte. In Largo del Nazareno turn left, cross Via del Tritone and take Via della Stamperia, bearing to the left. After 100 meters you will see the Trevi fountain on your right.

If you travel by bus, the nearest stop is San Claudio, at the end of Via del Tritone. The bus lines 492, 51, 52, 53, 62, 63, 71, 80, 83 stop here. The night buses N12, the N4 and the N5 also pass through here.

The Trevi Fountain is a monument in an open public square, and it is open to the public free of charge 24 hours a day.

The Trevi Fountain: your opinions and comments

Have you visited this monument? What does it mean to you? What advice would you give to a tourist?

The Trevi Fountain tickets

[…] 3. Trevifontein […]