11 February - 2 June 2025

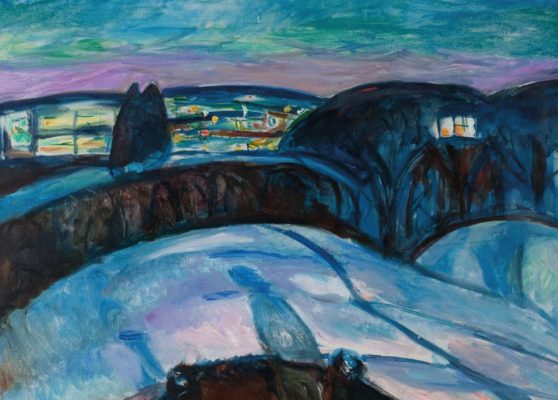

The exhibition “Munch. The Inner Scream”, scheduled at Palazzo Bonaparte from February 11 to June 2, 2025, offers a rare glimpse into the artistic journey of the great Norwegian master. It is an opportunity to closely explore the inner world of Edvard Munch through paintings, drawings, and graphic works that illustrate the evolution of an artist who is a symbol of Expressionism.

The event taking place at Palazzo Bonaparte from February 11 to June 2, 2025, is a significant occasion for the cultural scene in Rome and for all art scholars and enthusiasts. It offers a comprehensive exploration of the work of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch. The capital, a crossroads of great exhibitions, is set to host an itinerary that not only showcases works of profound emotional impact but also provides a broader perspective on the human experience central to Munch’s poetics.

The exhibition aims to highlight both the stylistic and technical innovations and the profound interiority that define the artist, establishing him as a pivotal figure in Expressionism. Within the halls of Palazzo Bonaparte, visitors can engage with the personal dimension that made Munch a unique figure in art history, fostering an intense dialogue with the existential reality surrounding him.

The work of Edvard Munch is situated within a cultural and historical context marked by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period when new artistic impulses flourished across Europe. Alongside the avant-garde movements, a pictorial language emerged, laden with emotional tension and prioritizing the individual’s inner life. Expressionism, of which Munch is considered a precursor and proponent, developed from a need to overthrow naturalistic and academic conventions in favor of art that authentically and directly conveys inner emotions.

Munch’s poetics, rich in symbolic and psychological references, draw heavily from biographical experiences often marked by suffering, loss, and illness—central themes in many of his works. His ability to transform personal torment into a universal representation of anguish, solitude, and a longing for love is one reason his works remain captivating today. While “The Scream” (in Norwegian, “Skrik”) is perhaps his most famous work, Munch’s entire body of work is a succession of iconic images, such as “Madonna”, “The Sick Child”, “Puberty”, and “The Dance of Life”. These works reflect his pursuit of an increasingly simplified and incisive pictorial form capable of communicating human fragility directly.

Between the late 19th century and the early decades of the 20th, Edvard Munch lived in various European cities such as Paris, Berlin, and, of course, Norway, interacting with figures and movements that would transform art. Paintings by artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin influenced his choice of a palette with intense colors, as well as the expressive deformation of forms, which found new outcomes in the Fauves and German Expressionism.

In Berlin, in particular, Munch connected with artistic and literary circles open to innovation and exhibited in contexts that sparked debate around his work. Despite initial mixed receptions, he established the foundations of an autonomous language. The energy conveyed through colors and the tension in his lines, often clashing with traditional perspective, reflect a new perception of pictorial space and the human condition.

Edvard Munch’s art is characterized by undulating lines, sharp or blurred strokes, intense color fields, and dramatic lighting that project the psyche’s shadows onto the canvas. His use of mixed techniques—oil painting, lithography, woodcuts, and etching—demonstrates his versatility. He continually experimented with various expressive media, sometimes reworking printing matrices at different stages to create multiple versions of the same composition.

His use of vibrant marks and bold contours emphasizes the physical presence of his subjects, who often seem to emerge from undefined backgrounds, suspended in dreamlike or hallucinatory atmospheres. These elements are evident in both his portraits, which delve deeply into psychological penetration, and his group scenes, which reveal a sense of unease and relational tension.

Organized with the scientific rigor characteristic of an event of this caliber, the “Exhibition: Munch. The Inner Scream” offers a rare opportunity to immerse oneself in Munch’s most representative works. The exhibition’s title highlights a central aspect of his research: the expression of profound unrest, which becomes the voice of a transformative historical epoch. Visitors will traverse rooms designed to emphasize the emotional engagement elicited by each painting.

Drawn from international collections and museums, the works presented span from Munch’s early years to his maturity, offering a complete overview of how his style evolved over time. The carefully curated selection includes both well-known masterpieces and works less familiar to Italian audiences, providing an extensive understanding of Munch’s artistic scope. Particular attention is given to the intimate and spiritual dimensions where solitude and hope, turmoil and desire intertwine in continuous dialogue.

The rooms of Palazzo Bonaparte provide a highly evocative setting to enhance Edvard Munch’s art. The exhibition layout guides visitors through an increasing crescendo of emotional tension and intensity, reflecting the artist’s changes and experiments. Each room is dedicated to a key moment or theme in Munch’s oeuvre, promoting an organic understanding of his artistic journey and showcasing his diverse techniques.

The setup, inspired by the curators’ scientific rigor and philological attention to the works, aims to create a connection between space and themes. Contrasting colors, lighting effects, and informative panels deepen the analysis of the works and contextualize their historical and artistic significance. This approach highlights how Munch integrated European influences and reinterpreted them with his sensitivity over a long career.

The exhibition is divided into several thematic sections, each dedicated to a defining aspect of Munch’s poetics. It begins with his early works, where the influence of Impressionism and Symbolism is mediated by a naturalistic approach but already reveals emotional instability through bold brushstrokes and distinctive use of light.

Another crucial section focuses on illness and death, central themes in Munch’s work, stemming from his early experiences of painful family losses. Paintings like “The Sick Child” powerfully convey the anguish the artist felt, which profoundly shaped his imagination.

Additionally, the exhibition explores tormented love and interpersonal relationships, featuring female figures embodying seduction and fear, as well as a critical view of couple dynamics. Finally, significant attention is given to psychological introspection and the individual’s reflection within a vast, unknown cosmos, reaching its zenith in iconic compositions such as “The Scream” and “The Dance of Life”.

Within the landscape of European art, Edvard Munch holds a significant position for his ability to anticipate trends that would fully emerge only in later decades. Born in Løten, Norway, in 1863, he grew up in a family marked by dramatic events: the early deaths of his mother and sister profoundly influenced his imagination, leading him to reflect from an early age on existential themes of life’s transience, pain, and fear.

After attending the Royal School of Drawing in Kristiania (now Oslo), Munch came into contact with the bohemian circles of the city, learning how art could serve as a vehicle for protest and introspection. His early works, imbued with symbolism, already bore the marks of a break with academic conventions.

Munch’s style underwent a slow but significant evolution, during which he gradually abandoned perspective and naturalistic representation in favor of vivid colors, vibrant lines, and a deliberately distorted spatial construction. His figures became increasingly simplified, as if to suggest that the essence of a feeling does not require academic elaboration to manifest its full power. This pursuit was accompanied by a strongly autobiographical dimension, giving rise to a cycle of works known as the Frieze of Life, where Munch codified the fundamental themes of his poetics: love, anguish, jealousy, and death.

Hosting an exhibition of Edvard Munch in Rome, a city with an ancient artistic tradition, offers an international audience the opportunity to retrace a crucial phase of modern art in an undeniably fascinating architectural and cultural context. This event builds on the success of previous Italian exhibitions dedicated to the artist, including one held in Milan, where Munch’s exhibition at Palazzo Reale attracted significant interest from visitors and art professionals alike.

The new event in the capital seeks to build on this past experience, while expanding its content by focusing on new loans and offering a broader critical interpretation of the works. In this sense, Rome becomes a crossroads where Munch’s intimate and profound language is contextualized within the horizon of European art and the ongoing historical reinterpretation pursued by leading museums and cultural institutions worldwide.

The exhibition is set to capture the attention of anyone eager to delve deeper into the expressive universe of such a complex artist. There are several compelling reasons to visit. First, it provides an opportunity to closely observe iconic works that rarely leave the institutions that house them, allowing for a direct encounter with Munch’s intentional use of color and form. Additionally, the accompanying critical texts highlight the biographical context and symbolic content of the works, creating an ideal bridge between the artist’s sensibility and the existential questions common to every generation.

Finally, the exhibition invites visitors to discover Palazzo Bonaparte in a new light: the noble interiors, paired with art of profound emotional impact, offer a journey that promises to be both engaging and contemplative. The historic Roman spaces, steeped in history, host Munch’s paintings, fostering a dialogue between past and present, classicism and modernity, that enriches the visitor’s experience.

The “Exhibition: Munch. The Inner Scream” unfolds along a carefully designed path that emphasizes the main thematic points of the artist’s career. After an introductory section that frames Munch’s historical and family context, the exhibition moves on to showcase his early works, often characterized by more chiaroscuro brushwork and attention to scenes of everyday life. In this phase, the nascent psychological dimension that would later dominate his work becomes evident.

The heart of the exhibition consists of large Expressionist paintings, where themes of loneliness, anxiety, and incommunicability emerge. Here, colors become more dramatic, with strong contrasts and undulating lines that enclose almost sculptural figures. Works such as “The Girl on the Beach”, “Anxiety”, and “The Kiss” reflect a fragmented inner universe, populated by profound contradictions, which Munch brought to light through a painting style as powerful as it was essential.

Each room addresses a crucial aspect of Edvard Munch’s production, bringing together paintings, drawings, and graphic works. The section dedicated to pain and illness, for instance, emphasizes how Munch processed grief through painting, transforming suffering into images of profound pathos. The public will encounter small-format works, where faces are marked by tragic intensity, and large canvases where the human figure is immersed in a landscape that is at times metaphysical.

Another significant section revolves around the idea of destiny and the eternal feminine. The figure of the woman, often portrayed as an ambiguous presence, becomes a mirror of Munch’s anxieties and passions, encompassing themes such as desire, attachment, and loss. In contrast, group scenes depict femininity as a symbol of continuity and vitality, despite its potential fragility. This contrast between eros and thanatos, love and death, permeates much of Munch’s poetics and is presented in an organized manner within the exhibition.

An often underestimated but essential aspect of Edvard Munch’s production is his graphic work. Lithographs, woodcuts, and etchings play a prominent role in his activity, not only as a means of spreading his images to a wider audience but also as a way to explore the expressive potential of line and form more immediately. The exhibition allows visitors to admire graphic works that reveal Munch’s masterful use of inks and matrices, demonstrating how he achieved striking effects of light and depth.

In addition to contributing to the dissemination of iconic subjects like “The Scream” and “Madonna”, Munch’s graphic experimentation enabled him to play with the sense of repetition and variation of motifs, producing different versions that highlight the continuous evolution of ideas and moods. This aspect is a valuable piece for understanding the artist’s relationship with the concept of seriality, which is emphasized in the exhibition through comparisons and parallels.

The exhibition also aims to highlight the modernity of an artist who, while not part of the most radical historical avant-gardes, anticipated some of their fundamental concerns, becoming a spokesperson for a new sensibility. Munch dismantled the idea of reassuring, decorative painting, replacing it with a quest centered on the human being’s unrest and their conflicted relationship with reality. In this sense, he can be seen as one of the spiritual fathers of 20th-century art, an artist who, even in the late 19th century, challenged the classical conception of painting.

His influence was felt by various subsequent movements, starting with Die Brücke in Germany, and extending to many painters who championed a subjective expressiveness, willing to transcend the constraints of mimesis. The legacy of Edvard Munch thus reaches contemporary movements that explore themes of the body and existential discomfort, making him a vibrant and relevant point of reference even today.

Among Munch’s most significant contributions to modern art history is his intense portraiture, capable of capturing the emotional component of each subject with almost visionary precision. Whether in self-portraits or depictions of family, friends, and patrons, Munch’s faces appear burdened with undefined anxiety or, conversely, made mysterious by sharp lighting. This approach suggests that the artist conceived painting not as a reproduction of mere physical appearance but as a psychological excavation in which facial features are amplified or dissolved based on inner states.

In his self-portraits, Munch persistently explored his own image, documenting moments of sadness, frustration, and renewal. These works should not be seen merely as exercises in introspection but as a universal discourse on how humans confront their fears. In the exhibition, examples of these reflections on the self provide direct insight into the artist’s soul, capturing the evolution of his pictorial language and themes.

While often remembered primarily for his expressive power, Edvard Munch was also an innovator in formal terms, consistently experimenting with materials and techniques. His work is characterized by the layering of colors and rapid brushstrokes, sometimes sketch-like, which enhance the effect of immediacy. In the field of graphics, Munch manipulated wood and stone matrices almost sculpturally, outlining and carving forms to achieve unprecedented results.

Some print series demonstrate how the artist studied tonal variations and ink gradations, always seeking to emphasize contrasts and create atmospheres that were either dark or, conversely, subtle and undefined. This technical focus is reflected in the halls of Palazzo Bonaparte, where the processes behind the works are explored through detailed panels and captions, offering insights for scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Approaching the paintings of Edvard Munch means engaging with an expressive power that often transcends photographic reproduction. Indeed, the true intensity of the colors, their saturation, and the application of paint are often amplified when one has the chance to observe the artwork in person.

Among his most famous paintings, “The Scream” is often evoked as a symbol of modern anguish. Yet, seeing the different versions in person or encountering other works such as “Madonna” and “Vampire” allows one to grasp how the artist modulated the same themes of pain and desire in ever-changing nuances. The materiality of the brushstrokes, the imperfections, and the traces left by the brush become essential elements of a poetics that makes vulnerability an aesthetically significant aspect.

Confronted with such a vast and varied body of work, the audience can experience the exhibition on multiple levels. On one hand, there is the dimension of historical research, which invites visitors to contextualize Munch’s evolution in relation to contemporary European movements and the social changes of his time. On the other hand, the spiritual and emotional components of Munch’s art emerge as an authentic testimony to a sensitivity that shakes rational certainties and compels the viewer to confront their own feelings.

For art history students, a visit to Palazzo Bonaparte can become a valuable opportunity for deeper study: analyzing brushstrokes, closely observing printmaking techniques, and studying the subjects and iconographies offer a rich repertoire of insights. For visitors with a more general interest, encountering Edvard Munch provides a privileged gateway to universal existential questions, such as loneliness, fear, and the desire to love and be loved.

Over the course of the 20th century, critics recognized Edvard Munch as a pivotal figure in the definition of Expressionism. From the early years of the century, his paintings sparked heated debates: while some deemed them excessive and unsettling, others among artists and writers immediately understood their revolutionary significance. Today, he is universally regarded as one of the greatest exponents of modern painting, a master who bridged the Symbolism of the late 19th century and the avant-gardes of the 20th century.

Scholars highlight how his art paved the way for a new conception of the representation of the body and emotion. In Munch’s paintings, the body is never merely an anatomical subject: it is also a vehicle for thoughts and feelings that surface on the pictorial plane. This shift influenced many later artists, from the figures of German Expressionism to post-World War II creators striving to express the states of human alienation and discomfort in increasingly complex societies.

Tracing the paths of contemporary art, one finds clear evidence of Edvard Munch’s influence. His expressive distortions, choice of bold colors, and daring compositional cuts are echoed not only in the historical movements of Abstract Expressionism and New Objectivity but also in certain strands of more recent figurative painting. Painters, photographers, and performance artists of subsequent eras have drawn on Munch’s lesson on the revelation of interiority.

The “Exhibition: Munch. The Inner Scream” thus offers the opportunity to observe the genesis of a language that, although born in a different context, still lends itself to contemporary interpretations. The thread connecting Munch’s work to current explorations lies precisely in his urgency to express existential unease, the tension between identity and otherness, between joy and torment. These themes span decades, continuing to challenge art and the sensibilities of today’s humanity.

Your opinions and comments

Share your personal experience with the ArcheoRoma community, indicating on a 1 to 5 star rating, how much you recommend "Munch. The Inner Scream"

Similar events