The Sistine Chapel ceiling in the Vatican houses the wonderful frescoes made by Michelangelo Buonarroti. Let’s discover the history, the frescoes and the restorations.

Location:

Vatican City, ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

Built by:

Painted by Michelangelo between 1508 and 1512 CE

What to see:

Creation of Adam, Prophets and Sibyls, Genesis scenes

Opening hours:

Monday to Saturday, 9:00 – 18:00

Price:

Standard ticket from 12 to 21 euros

Transport:

Metro station: Ottaviano

Top selling tickets on ArcheoRoma

The history of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling describes two distinct phases: one from the 15th century and another from the early 16th century, created by Michelangelo.

The first painting of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling dates back to 1481 and was commissioned by Pope Sixtus IV. The ceiling was decorated with a starry sky by the Amerini painter Piermatteo di Manfredi, also known as Piermatteo d’Amelia or from Amelia (Amelia, 1445-1448 – c. 1508).

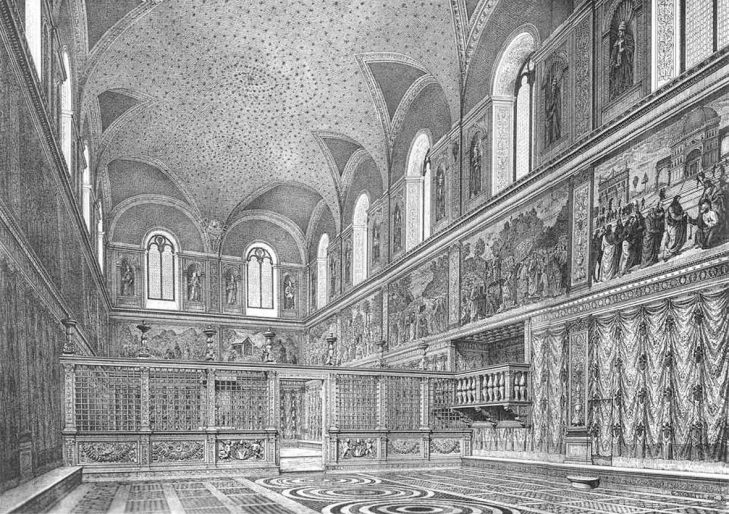

In the engraving in Fig. 1, we can see the Sistine Chapel Ceiling decorated with the starry sky, the presence of two windows on the west wall (which were later removed by Michelangelo), and the railing in a central position (later moved toward the entrance on the east wall).

During the early 1500s, the Sistine Chapel Ceiling suffered damage due to the instability of the foundations, inherited from the ancient Cappella Magna, dating back to the late 1200s. The damage was likely caused by the works for the new St. Peter’s Basilica, located just a few meters away. The decorations by Piermatteo d’Amelia were irreparably ruined by a crack in the ceiling.

The ceiling was restored by Bramante using a series of metal chains and filling the crack with mortar and bricks. Pope Julius II at the time decided to redecorate the ceiling and entrusted the task to Michelangelo Buonarroti. Michelangelo had fled to Florence a few months earlier due to his deep disagreement and disappointment with Julius II, who had halted the works on the papal tomb, which was to be placed in St. Peter’s Basilica (it was later completed in a reduced form by Michelangelo in the last years of his life and placed in St. Peter in Chains).

However, the ambition of the project convinced Michelangelo to return to Rome, and the contract was signed between March and April 1508.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, March 6, 1475 – Rome, February 18, 1564) was a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet who painted the marvelous Sistine Chapel. He was the same artist who created the David, Moses, the Pietà, and the Dome of St. Peter’s.

While the Florentine master Piero di Jacopo Rosselli prepared the surfaces of the dome, Michelangelo spent the first few months creating preliminary drawings. The original plan included representations of the twelve apostles on the large architectural thrones that overlook the pendentives, while the ceiling was to be decorated with geometric elements.

Unfortunately, most of the preliminary drawings were burned at Michelangelo’s request, according to his biographer Giorgio Vasari. It is said that Michelangelo did not want the public to realize how much work he had put into creating his masterpieces, as it could have diminished the idea of his creative genius. Another theory is that the artist did not want competing artists to use the preparatory sketches for study purposes (notably, two young sculptors stole 60 preliminary drawings from his workshop in Florence, which were later returned).

Only two preliminary drawings have survived.

The first shows one of the twelve apostles above the pendentives (where today we find the prophets). It is probably a seated nude, and the geometric elements that would make up the ceiling are clearly visible. The drawing is kept at the British Museum in London (1508). Dark ink (study of the ceiling) and black chalk (arms and hands, presumably attributed to the figure of Adam) 1.

The second shows a study for the niches, now kept at the Detroit Institute of Arts in Detroit, Michigan, USA. Dated 1508. Dark ink and chalk on handmade paper.

An early design for the scaffold necessary to easily reach the ceiling was created by Bramante. It was a suspended scaffold anchored by ropes to the ceiling. Criticized by Michelangelo due to the inevitable holes for the hooks, it was replaced by an alternative design by Michelangelo.

This was a wooden scaffold anchored to the side walls of the chapel by self-supporting trusses. This solution covered half of the Sistine Chapel and consisted of six pairs of trusses supporting a walkable surface with steps.

While this solution was practical because it covered a large area, it forced the artist to work under difficult conditions and body positions. The natural lighting was nearly nonexistent, and it was necessary to rely on candles and lamps, which created uneven lighting.

The work progressed from the entrance wall toward the altar wall.

The first application of lime and pozzolana mortar (instead of lime mixed with sand) was not a good choice. The diluted mixture and slow drying time caused mold to appear. The plaster had to be completely removed and reapplied. The final plaster was a mixture designed by Jacopo Torni (called Jacopo Fiorentino or l’Indaco, a student of Domenico Ghirlandaio) of lime and pozzolana on a rough coat made with the same mixture. Only in the lunettes was marble dust used without a rough coat 2.

For the transfer of the preliminary drawings to the plaster, Michelangelo used two different methods.

Dusting. This method involves creating a series of holes with an awl following the lines of the 1:1 scale drawing. These reference points were then highlighted on the plaster by tapping a bag of fine black charcoal powder onto the drawing. This method was mainly used for drawings that required more accuracy, such as hands and faces.

Indirect engraving (or tracing). This method was mainly used for central elements like the Creation. It involves transferring the drawing directly to the plaster by tracing the outlines with a metal point.

On June 26, 1511, Pope Julius II della Rovere returned to Rome from Rimini to announce the opening of the Ecumenical Council (Fifth Lateran Council, aimed at restoring ecclesiastical unity), which would take place the following year at the Basilica of St. John Lateran. On this occasion, he had the scaffolding dismantled to reveal the first half of Michelangelo’s work, which was examined by the Pope between August 14 and 15 of that same year.

This occasion was valuable for the artist to update the size of the figures for the continuation of the work, as they were rather small and hard to read.

In October 1512, Michelangelo sent a letter to the Pope informing him that the Sistine Chapel was completed. The work was completed by Michelangelo in 1512, just under a year before Pope Julius II passed away (February 21, 1513).

On October 31 of the same year, the chapel was reopened for the celebration of the Vespers liturgy, on the eve of All Saints’ Day.

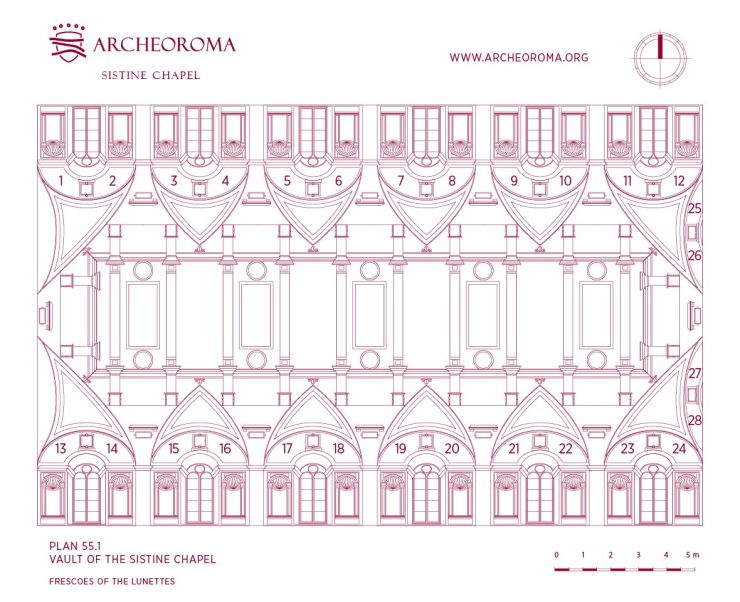

The lunettes represent the semicircular frame around the arch of the windows on the lateral walls of the Sistine Chapel, positioned above the niches of the popes. Although they technically do not belong to the ceiling, they are included here due to their iconographic coherence with the rest of the ceiling.

The lunettes of the Sistine Chapel were painted by Michelangelo using the same wooden truss scaffold designed for the ceiling painting. These are the frescos painted more hastily, to the point that no transfer method was used on the plaster, except for the central plaques.

They represent, as with the sails, the generations of Christ’s ancestors. On the sides of each lunette, individual seated figures are depicted, separated by plaques identifying them in Latin.

Just like for the popes in the lunettes, the progression of the lunettes should be read alternately, starting from the altar wall toward the entrance wall.

Note that the first two lunettes on the altar wall were removed by Michelangelo in 1537 during the preparation of the plaster for the creation of the Last Judgment.

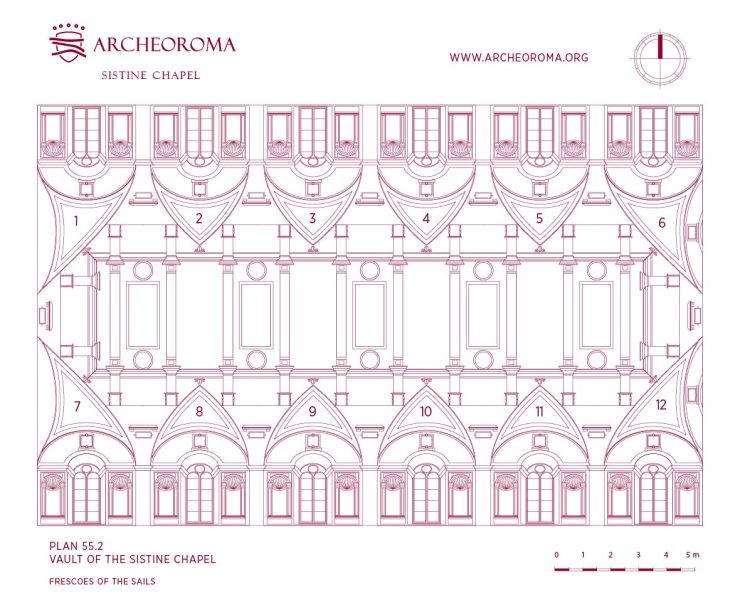

The sails are triangular-shaped concave spaces that connect the lateral walls of the Sistine Chapel with the lowered barrel vault. Like the lunettes below, they represent the forty generations of Christ’s ancestors, taken from the Gospel of Matthew.

They depict compositions of family groups, men and women representing humanity and the succession of generations. Each sail is topped with two symmetrical bronze nudes and bucrania (ox skulls, which represent sacrificial rituals).

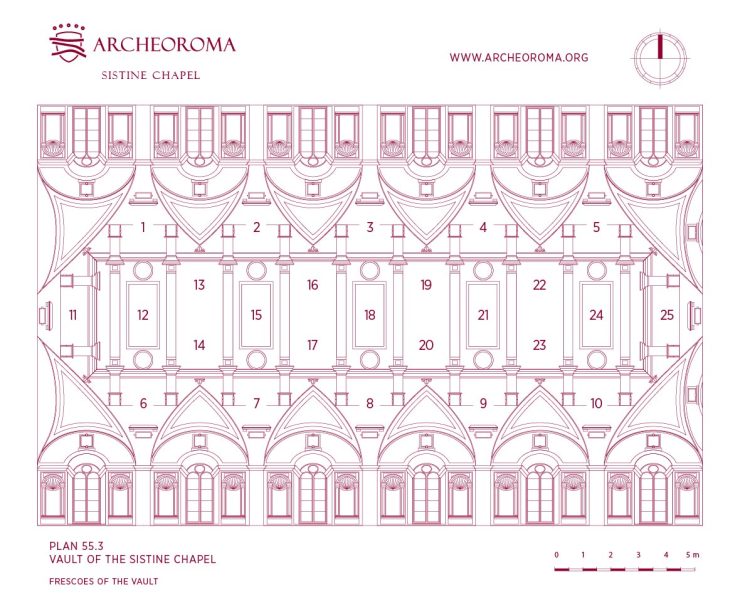

The ceiling is horizontally divided into nine panels, depicting the stories from Genesis, arranged chronologically starting from the altar wall. There are five larger panels, each containing two figures, interspersed with four smaller panels containing a frame surrounded by two medallions and four seated figures.

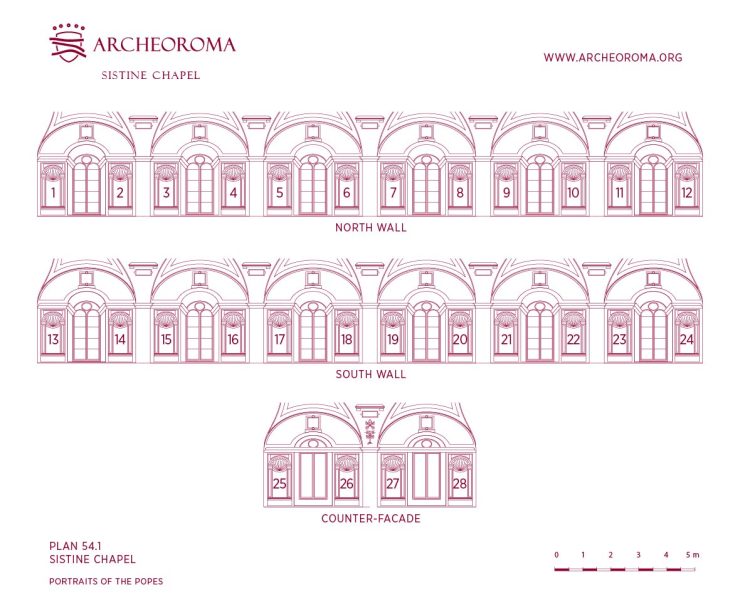

In the third order of the Sistine Chapel, the niches house the portraits of the Popes, which form one of the most significant components of the wall’s painting decoration. These frescos were painted in the 15th century by master painters such as Pietro Perugino, Sandro Botticelli, Cosimo Rosselli, and Domenico Ghirlandaio, with the aim of honoring the apostolic succession and the central role of the papacy in the Catholic Church.

The niches, located between the arched windows of the lateral walls and the counter-facade to the east of the building, house portraits of twenty-eight popes. Each figure is placed in a niche that serves as a base for the upper lunettes, created by Michelangelo. The overall structure of the decoration aims to establish a visual and symbolic relationship between the popes and the biblical stories depicted on the ceiling and in the Last Judgment.

The iconography of these images follows a precise chronological and alternating scheme, with a change in rhythm only in the first section, toward the altar, where the first two popes are painted on the left wall, breaking the alternation between right and left that characterizes the rest of the layout. The succession of popes, starting from the third pope, Anacletus (76 – 88 AD), and reaching Marcellus I (308 – 309 AD), reflects a meditation on the continuity of the Church and the papacy, highlighting the connection between the popes and the apostolic tradition.

Technically, the papal portraits are inserted with great attention to architectural integration. The niches are not just decorative spaces, but functional elements that support the entire pictorial composition. The use of architectural space and the dialogue between painting and the wall structure are fundamental elements to understanding the artistic conception of these frescos. The choice to depict the popes in a position of authority, within niches that give depth and solemnity to the figure, reflects the intention to reinforce the idea of a Church that endures over time, under the guidance of its pastors.

The Creation of Adam is the most famous composition of the ceiling, depicting the encounter between the divine and the human, and the moment of creation. Adam, lying on the ground, reaches out his hand toward the divine being, wrapped in a pink drapery, until their fingers touch.

This is the series of frescos decorating the pendentives, the hanging capitals between each sail. In the space between two plinths with false high-reliefs of pairs of putti, the seers, i.e., sibyls and prophets, are depicted, each accompanied by a pair of young assistants.

The Sistine Chapel Ceiling underwent several restoration interventions over the years. The reasons were not solely due to the natural deterioration of the frescos and colors but also the structural state of the Sistine Chapel. In 1522, only nine years after the completion of the work, the lintel on the entrance wall collapsed (killing a Swiss guard), while during the 1523 conclave, there were significant collapses on the ceiling.

The first restoration work began in 1543.

During the 1565 conclave, large rips were made in the ceiling.

In 1625, a restoration was entrusted to Simone Lagi, whose task was to remove the dark patina that had formed over the years on the frescos using a linen cloth and breadcrumbs.

Between 1710 and 1713, another restoration was assigned to the painter Annibale Mazzuoli, carried out in collaboration with his son using sponges soaked in “Greek wine” and repainting details, including those lost due to efflorescence of saltpeter (a phenomenon where water evaporates from crystallized salts on the surface of plaster, causing the surface to detach).

Between 1935 and 1938, the Vatican Museums’ restoration laboratory initiated another phase of repair and cleaning of surfaces on the eastern part of the Chapel.

In 1979, the largest restoration project of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling began. This work was entrusted to a team of experts led by Gianluigi Colalucci, based on the guidelines written in 1978 by archaeologist and director of the Vatican Laboratory for the Restoration of Paintings Carlo Pietrangeli.

For the restoration, aluminum scaffolding was created, anchored to the lateral walls of the Chapel using the same holes in the walls used for Michelangelo’s scaffolding.

Ceiling: your opinions and comments

Have you visited this monument? What does it mean to you? What advice would you give to a tourist?

Tickets

Wonderful synopsis of the chapel and Michelangelo’s work. If you are able to do pre-recorded video tours, I would love to get one for my art history class!